http://www.ryzhakov.co.uk/zwinger-art-thriller-elena-kostioukovitch//#artthriller

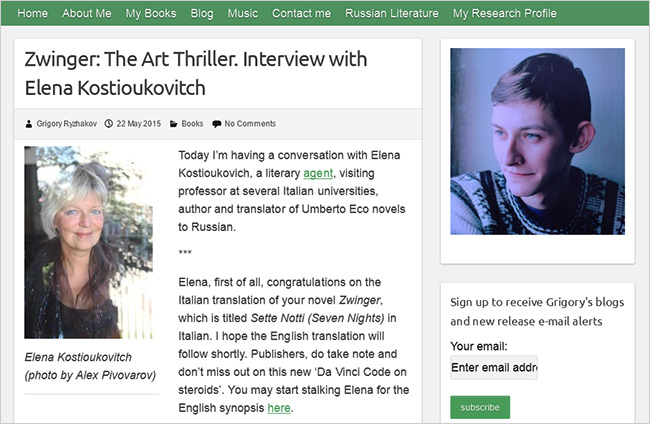

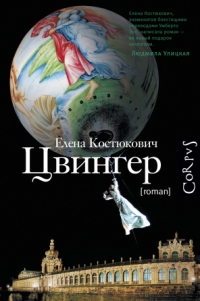

Zwinger: The Art Thriller. Interview with Elena Kostioukovitch

Grigory Ryzhakov

Today I’m having a conversation with Elena Kostioukovich, a literary agent, visiting professor at several Italian universities, author and translator of Umberto Eco novels to Russian.

***

Elena, first of all, congratulations on the Italian translation of your novel Zwinger, which is titled Sette Notti (Seven Nights) in Italian. I hope the English translation will follow shortly. Publishers, do take note and don’t miss out on this new ‘Da Vinci Code on steroids’. You may start stalking Elena for the English synopsis here.

Jokes aside, my first question is why Zwinger? Elena, you have a prominent profile in the international literary establishment, and becoming an author and writing an novel that deals with Holocaust, KGB and other disturbing memes, is quite daring. And you expose your family history there too. So what is the story in a nutshell and what made you write and publish it?

I’ve been thinking of turning my family history into a narrative for a long time. I consider this a curious game, the game I love, a way of communication with the reader. In my opinion, the best kind of writing is creating texts with elements of fiction yet containing references to the real events.

You may ask me why I decided to write a novel but not a biography or a chronicle if facts are so dear to me. The answer is simple: there are always gaps between the facts. And those are nothing to fill up with, apart from fiction. For that reason, any biographies feature made-up things, versions, opinions, hypotheses, i.e. fiction.

So I thought it’d be honest to call all this a narrative, and fill the gaps with details and connections, so dear to our hearts, made-up details.

Why have I chosen to base it on the family history? Only from this factual material I can mold though fictitious yet quite accurate details and links. I know everything intimately in this history, from the inside. So I don’t make things up randomly.

That’s exactly the main story line of the novel: the old hasn’t died, it still lives inside the new, like our ancestors live inside us, and something they couldn’t tell we can shout out. It’s important to think it through, to invest yourself into and live in this old experience.

Sometimes, when you are tired you can get into complex parts of your consciousness. When you are tired, the brakes of shame and fear are gone. The main protagonist of Zwinger, Victor Zieman, my alter ego, gets mentally overloaded during the book fair, gets so tired that his mind makes him see things: suddenly he finds a solution for some mysterious questions, he was at lost with when he was sober.

In parallel with Victor, my reader gets overwhelmed too. I create a flood of information, similar to what Victor gets, that crushes his nervous system.

In Zwinger, the main protagonist, Victor, finds himself unravelling mysteries. You have been translating Umberto Eco. What impact did Eco’s writing have on you, your writing style, voice and narrative?

I think you are right about this; my novel is narrated by one of the regular Eco’s characters – an intellectual, left-wing, dreamer burdened with psychological complexes. Such characters narrate their stories, from the first persons point of view, in Foucault’s Pendulum (Casaubon), The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana (Bodoni) and Eco’s latest novel, Number Zero (Colonna). I don’t know if many readers noticed but his characters’ last names represent the names of (Word) fonts, which underlines the artificial, fictitious nature of Eco’s narrators.

This type of character in Russian I needed to arm with special language, which I molded out of my own reading, student jokes, even my family folklore. Out of the humor. I constructed this language for my Eco translations for thirty years.

But, as it turned out, this language has taken over me. When it came to a decision of how my character will be conversing – a troubled intellectual – I realized that the language I bestowed upon Eco’s characters is the most natural and the only possible one. So, I opened the tap and the language flowed.

Zwinger features many flashbacks, one of them is the funeral of Vladimir Vysotsky, the beloved Russian b ard, in Moscow during the Olympics in 1980. Was this written based on your personal memory and what role does this subplot play in the novel?

ard, in Moscow during the Olympics in 1980. Was this written based on your personal memory and what role does this subplot play in the novel?

Of course, Vysotsky’s funeral, Moscow Olympics, fake Pravda, teaching students on Russian course in Milan, Frankfurt book fairs, the Babi Yar commemoration events and so on – these are all my personal memories of things I felt and lived through.

As what one might expect from a translator of your caliber, you operate with a massive vocabulary in Zwinger: the novel contains many references to history, art and the world of publishing – what I call ‘the elitist bits’. I think these ‘bits’ are important as they show the author has researched the subject well, and also they add authenticity to the novel. How do you decide on the balance between the story plot, the characters and these ‘elitist bits’, the balance between a story and an essay?

I needed to re-start the readers’ memory, to overwhelm them to the same extent as my protagonist is tortured by erudition, new information and troubling memory.

Half-mad from all the haste, disease, lack of sleep and skipped meals, Victor enters a state of trance, his intuition takes over the reins, and he finds answers for mysterious questions, which his normal state was unable to solve.

Akin to Zwinger, your own life is a roller-coaster that landed you in Italy. How did this happened, Elena? Why did you swap Russian winters for Mediterranean splendours?

Your question is on point here. I’m not very fond of cold Moscow winters. I was born in Kiev, winters are warmer there. So, during my Moscow years the cold had been an issue for me. And frankly speaking I have never loved anything, even Russian literature, even any of my admirers, as much as I love Italy: I have fallen with her from the first sight.

Remember, Gogol once wrote about Italy, ‘Russia, snow, rascals, the department – I must have dreamt of them in my sleep and then I woke up in my Motherland.’

There was a technical issue: How to make Italy love me in return? So we gave each other something. And there it was. Italy gave me my children, its vast lands, lines and colours, scents and sounds. I gave her my work. I wrote a book on Italian food, now I am writing another on sculpture, architecture; with God’s help, I’ll finish it in three years or so.

Do you think the differences between Russian and Italian mentalities find their reflections in the national cuisines? What makes a dumpling Italian, Ravioli, or Russian, pelmeni?

Ravioli is an Italian dish mainly because it belongs to the Italian enormous culinary symphony, in which this dish is one of the instruments in the orchestra, colors of the palette.

‘Raviolo’, a speciality in Marche, is called ‘agnolotto’ in Piedmont, ‘anolino’ in Parma, ‘marubino’ in Cremona, ‘tortello’ in Emilia, ‘pansoto’ in Liguria, ‘tordello’ in Toscana, ‘cappellaccio’ in Ferrara; and in each region they use a distinct sauce and spice for ravioli, as well as specific shape and color of the plate. And Italians appreciate and like the fact that in the neighbor region the same food is called a different name. The same concern paintings: even an Italian person not specialised in the art easily discriminates between Siena and Toscana styles, and those from the Venetian, and the Ferrara style from the rest. And, while in the museum, he enjoys the way paintings by different schools are exhibited side by side.

Considering your impressive work in the past, you have, no doubt, tremendous future plans as a writer and a translator. What can we expect from you next?

Of course, I have been thinking about a grand project. I don’t know whether or not I’ll have strength and time for it. It is a huge work, a kind of travelogue on different regions and topics: sculpture, architecture, iconology. I want to do this, so the travelers who read the book could see each and every town in Italy in their bright distinct light.